Fascinating history along a short section of Whitechapel Road.

The Royal Oak – once called The Morocco Slaves

The Royal Oak, 120 Whitechapel Road, was previously called the Morocco Slaves. It became the Royal Oak in the 1750s. All those pubs called the Royal Oak get their name from the time the future King Charles II went on the run and hid in an Oak Tree after losing the Battle of Worcester big time in 1651. He later escaped to France on a coal boat from Shoreham.

Just to the left of the current Royal Oak building, a large house at No’s 118–120 Whitechapel Road, was the public house known as the Morocco Slaves in 1730. It later became the Royal Oak.

In an article on Discovering Bristol I read that English sailors were extremely reluctant to work on slaving ships. It was a dangerous and risky business. They were tricked into it by pub landlords working in collaboration with ship’s captains.

Ships which sailed too close to North Africa risked capture by Barbary pirates. The English sailors would be sold as slaves. Occasionally their friends could come up with the ransom money. The Wikipedia page for Barbary Pirates says that in the early 1600s there were around 35,000 European Christian slaves being held across Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. “The majority were sailors (particularly those who were English), taken with their ships…” Scary stories must have been circulating on the Thames riverbanks.

The Treaty between Great Britain and Morocco of 1721

The sultan had hundreds of slaves who were captured English seamen. King George I sent a Royal Naval Officer, Charles Stewart, to negotiate with the sultan. The Treaty, written in Spanish, was signed aboard HMS Dover. It said that: “the English may now, and always hereafter, be well used and respected… all the English Ships may pass and repass the Seas without hindrance”.

Stewart then had to go inland to negotiate the release of 296 seamen. A big celebration was held when they arrived in London. I’d say that this event was why the pub was named (or renamed) the Morocco Slaves

The Licensing Act of 1737 allowed straight drama to be performed at only two theatres – Drury Lane and Covent Garden. Even then it was subject to censorship by the Lord Chamberlain. Poor Robert Walpole, the prime minister, didn’t like being satirised. There was a get around – musical interludes. East End theatres could operate as music halls. The Theatrical Regulation Act, 1843 allowed other theatres to put on plays, but they had to submit them to the Lord Chamberlain seven days in advance. Unsurprisingly there were plenty of illegal performances in the East End.

In 1849 Richard Riley Cragg sought a Music License for the Royal Oak. Then in 1868 local ginger beer maker, Zebedee Wilcox, converted the upstairs into a music hall. Two years later he built the much bigger Wilcox’s New Music Hall to the rear of the pub. It could hold 700 customers, and was hugely successful. Sadly Zebedee Wilcox died in December 1873. The new owner was George Robinson who had been running the rival Wilton’s Music Hall. He pulled down the old pub and built the building you see today. The music hall in Vine Court (out the back) was closed and became a Lithuanian Synagogue from 1892 to 1965.

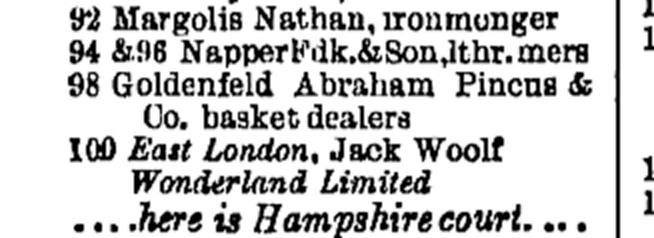

Wonderland – Ravoli Cinema – Ibis Hotel

Embed from Getty ImagesThe photo above was taken in Wonderland in 1903.

Wonderland was a big East End hall at 100 Whitechapel Road. Jack Woolf introduced the very popular boxing in the late 1890s. 100 years before it had been a pub called the Earl of Effingham. The 3rd Earl of Effingham, Thomas Howard, was the Master of the Mint at that time. By the 1860s William Booth was preaching in a hall at the back. A 4,000 seat theatre replaced the pub soon after, but it burnt to the ground in 1879. Eventually it became the 3,000 capacity hall for boxing, Yiddish theatre, and other uses. It was destroyed by fire again in 1911.

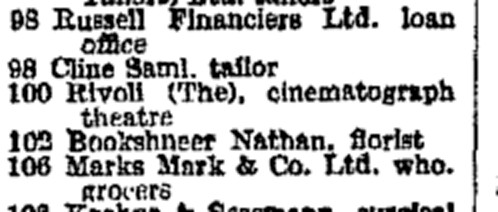

In 1921 a big 2,230 seat silent cinema, The Rivoli Cinematograph Theatre opened on the site. It was very special. German bombs destroyed it in 1940.

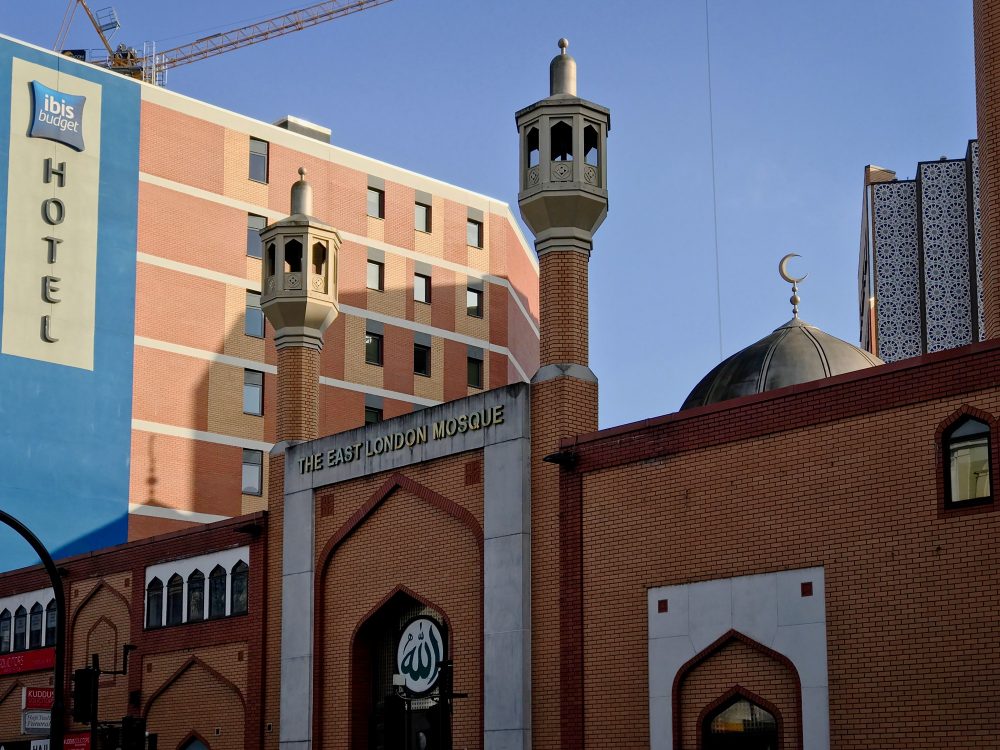

East London Mosque

In Edwardian times I read that there was no indoor space for Muslim worship in London. As a quick test I searched the 1910 Post Office Directory. No sign of a mosque. In 1910 Ameer Ali, a judge, and Islamic scholar, invited prominent Indian Muslims to a meeting in the Ritz. A top hat and tails affair. The result was the establishment of the London Mosque Fund.

In the 1930s the East End, with it’s proximity to the docks, housed the largest Muslim population in London (500 – 1,000). They were mostly Asian sailors, known as Lascars at the time. The Old King’s Hall at 85 Commercial Road was rented for Friday prayers. Three adjacent Georgian terraced houses (446–450 Commercial Road) were later purchased and converted. On 1st Aug 1941 the East London Mosque and Islamic Cultural Centre opened. It had capacity for about 400 in the prayer hall.

In 1974 Sulaiman Mohammed Jetha, Chairman of the East London Mosque Trust, managed to get hold of some land at 43-45 Fieldgate Street, and a temporary single storey mosque with capacity for 320 was built.

The current East London Mosque at 82–92 Whitechapel Road opened on 12th July 1985. It had a capacity for 2,000 at prayer. Just over half of the £2 million cost came from King Fahd of Saudi Arabia. South of the site, the square, domed prayer hall, is angled at forty-five degrees to the Whitechapel Road. The rear (south-east) wall faces the Ka’bah, the building at the centre of the Great Mosque of Mecca.

East London Mosque has a single 100ft minaret. It was the first mosque in Britain to broadcast the daytime call to prayer through public speakers.

In 1999 the Mosque acquired the site next door and in 2004 the new London Muslim Centre opened, greatly expanding the space available. In 2013 the Maryam Centre, home to the prayer facilities for women, opened to the public, increasing the capacity for prayers to 7,000 across the site.