On Tuesday 10th Oct the Geezers enjoyed a very informative visit to the Thames River Police Museum at 98 Wapping High Street. The Thames Police were founded on this very site in 1798, and are still here! They’re now called the Marine Policing Unit.

The museum is run by retired volunteer curators and is inside a working police station, so visits have to be arranged in advance. It’s a 3 min walk west of Wapping Overground Station.

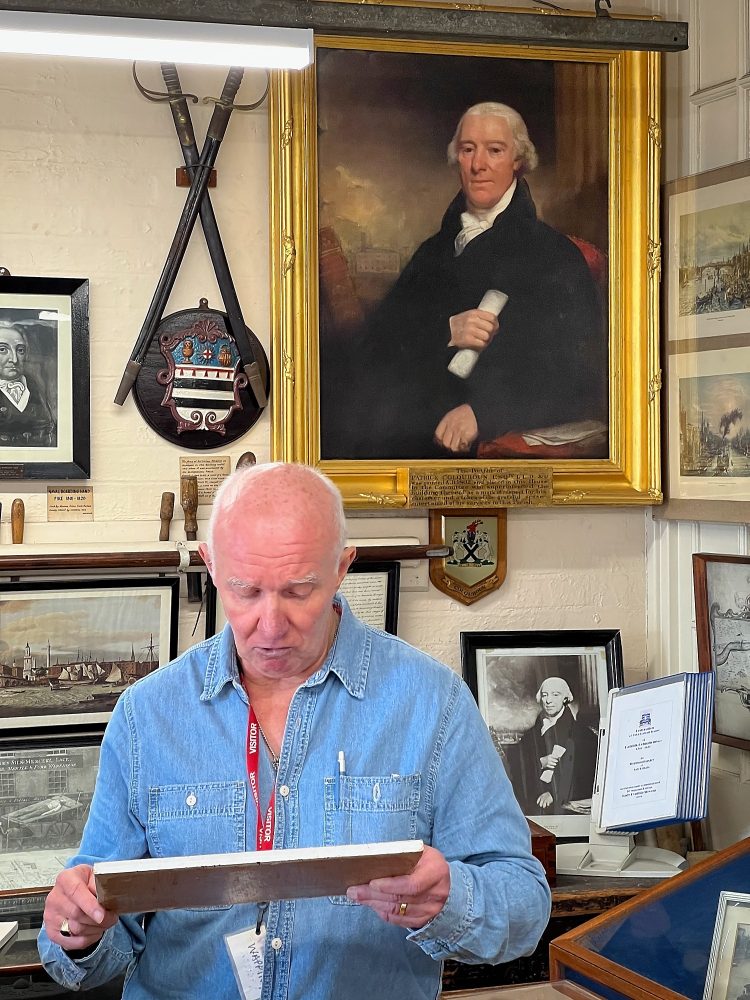

Robert Jeffries, who had served in the Met Police from 1973 -2005, came outside to take our group into the museum. Rob was accepted into Thames Division (as it was then known) as a recruit in 1988 and began his training on the boats.

The Thames River Police prior to 1839

Rob took us back to the 1790s to explain how the Thames River Police was founded in 1798, 31 years before Sir Robert Peel’s “Bobbies”.

Patrick Colquhoun (1745 – 1820) led an amazingly active life. He was born in Dumbarton, near Glasgow, sent to America, and returned to Glasgow aged 21 to set up a linen trading business. In 1782 he built himself the enormous Kelvingrove House. He was Lord Provost of Glasgow from 1782-4.

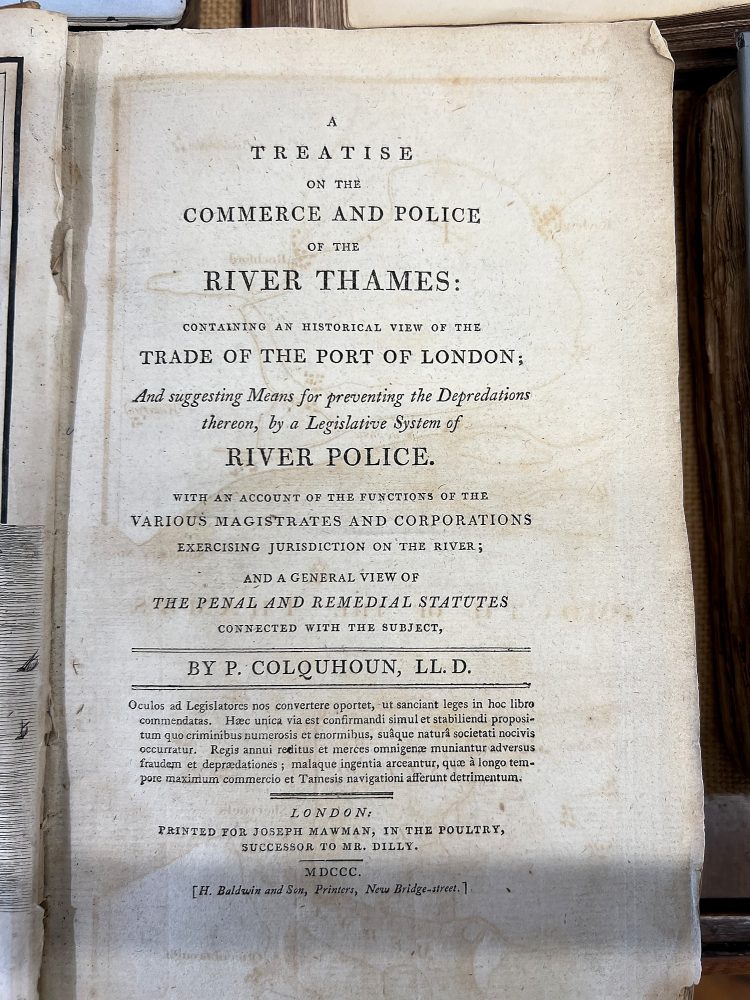

Colquhoun was a statistician, collected economic data, and lobbied the Prime Minister, William Pitt on behalf of businesses. In 1785 he moved to London. In 1796 Colquhoun published “A Treatise on the Police of Metropolis”.

Ships anchored in the Thames to unload cargo were very vulnerable to both organised crime and casual crime – where underpaid workers regarded stealing something as a perk of the job. Rob said that in the 1790s about £500,000 a year was being lost to theft – which would be about £96 million today.

Various attempts at policing the river came to nothing because of fears over the cost to the Government (taxation), civil liberties and corruption.

Rob told us that the most valuable cargo coming into London came from the West Indies. About 100,000 tons of sugar and 2 million gallons of rum was being imported each year from the West Indies in the late 18th Century. Obviously organised criminals targeted these ships. The stolen goods carried a lot of import duty, so the Government was also losing money.

Since the Government showed no interest in policing the Thames, Patrick Colquhoun, along with JP and master mariner, John Harriott, and philosopher/lawyer, Jeremy Bentham, persuaded the West India Merchants to fund a Marine Police Force for a one year trial in 1798. Colquhoun acted as Superintending Magistrate and Harriott the Resident Magistrate.

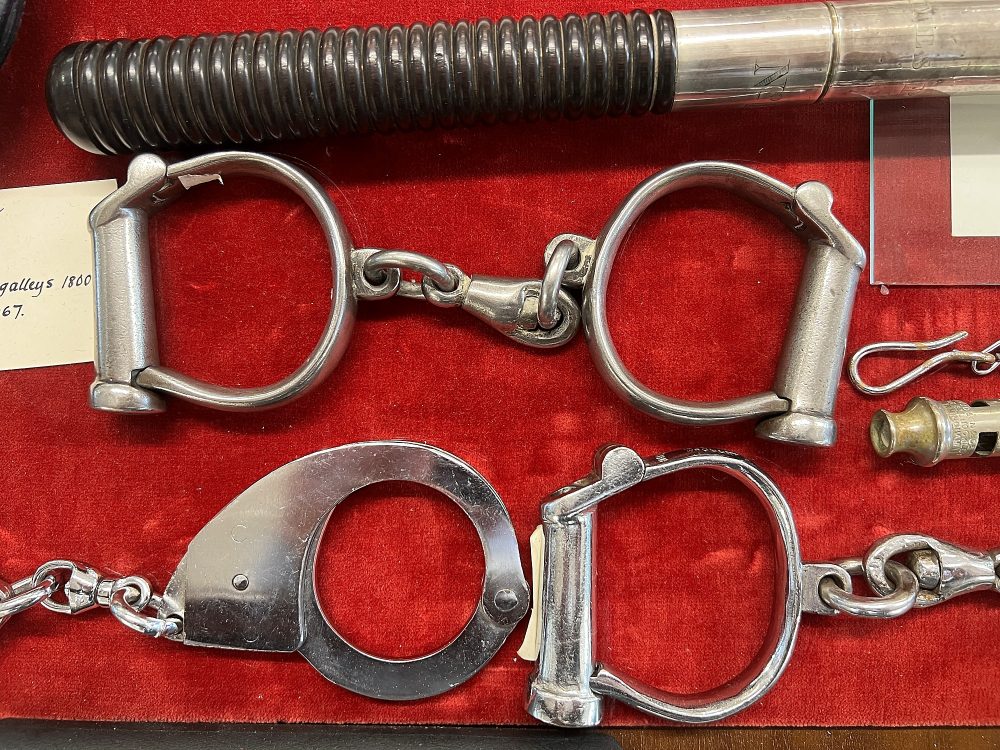

They began with a number of rowing galleys, each manned by a Surveyor (Inspector) and three watermen Constables. The Surveyors were empowered by the Crown and were issued with an excise warrant by Customs and Excise. They also employed guards on West India ships and on the quayside to prevent petty theft.

This first police force was greatly outnumbered by, and received a hostile reception from the people who worked on the river. But at the end of the year Harriot gave a report to the Home Office which said: “..instead of many waterman’s boats hovering nearby while ships unloaded, the river now appears quiet and peaceful, except for those going about their lawful business.” For an investment of £4,200 they’d saved £122,000 of cargo from theft, as well as several lives.

As a result of this success in 1800 Parliament passed the Marine Police Bill. The government took over funding the Marine Police and increased its number of officers from 50 to 88. Patrick Colquhoun’s good work was copied around the world.

To sell his ideas to a sceptical Government Patrick Colquhoun had used cost-benefit arguments. He introduced the idea of crime prevention or preventative policing as a fundamental principle of policing. The rowing galleys and guards deterred thieves.

As a serving officer of 32 years Rob Jeffries said that offences against the person concern us more today.

Policing on land & Robert Peel

Rob told us that way back in 1285 a law was passed which established a system of local law enforcement that required each county to appoint a group of officials to pursue and apprehend criminals. He said that this worked reasonably well until the industrial revolution when big towns and massive population movements brought poverty and crime.

Robert Peel was first elected as an MP by just 24 electors in the rotten borough of Cashel, Tipperary! He soon changed constituencies to Cheltenham (1812), then Oxford University (1817).

He was a good speaker and was Home Secretary to the Tory party 1822-30. He introduced a number of reforms: repealing a large number of criminal statutes, reducing the number of crimes punishable by death, and improving conditions for inmates in gaols. Today he’s remembered for founding London’s Metropolitan Police Force at Scotland Yard in 1829. It had 1,000 constables.

Expanding the Marine Police

The number of officers increased. Two old naval vessels enabled them to patrol between Chelsea and Woolwich. In 1817 a cutter was bought to patrol the lower reaches of the Thames including the Royal Dockyard at Sheerness. More marine police stations were established along the Thames.

1839 – Marine Police Force merged into the Metropolitan Police Force

It became the Thames Division of the Metropolitan Police.

Thames Police Steam Launches

The rowing galleys and sailing patrols continued for years. But trade on the river was increasing, and iron ships were replacing wooden ones. London was the largest city in the world between 1831 and 1925. The Thames was packed with ships from all around the world.

In Sept 1878 a coal boat, SS Bywell Castle, hit and sank SS Princess Alice, a paddle steamer which was returning to London Bridge on a pleasure cruise. She sank within 3 minutes near Barking Creek. Princess Alice had nearly 1,000 people on board; 640 bodies were eventually recovered, maybe 700 people died. There were no facilities on the river to deal with a disaster of this scale.

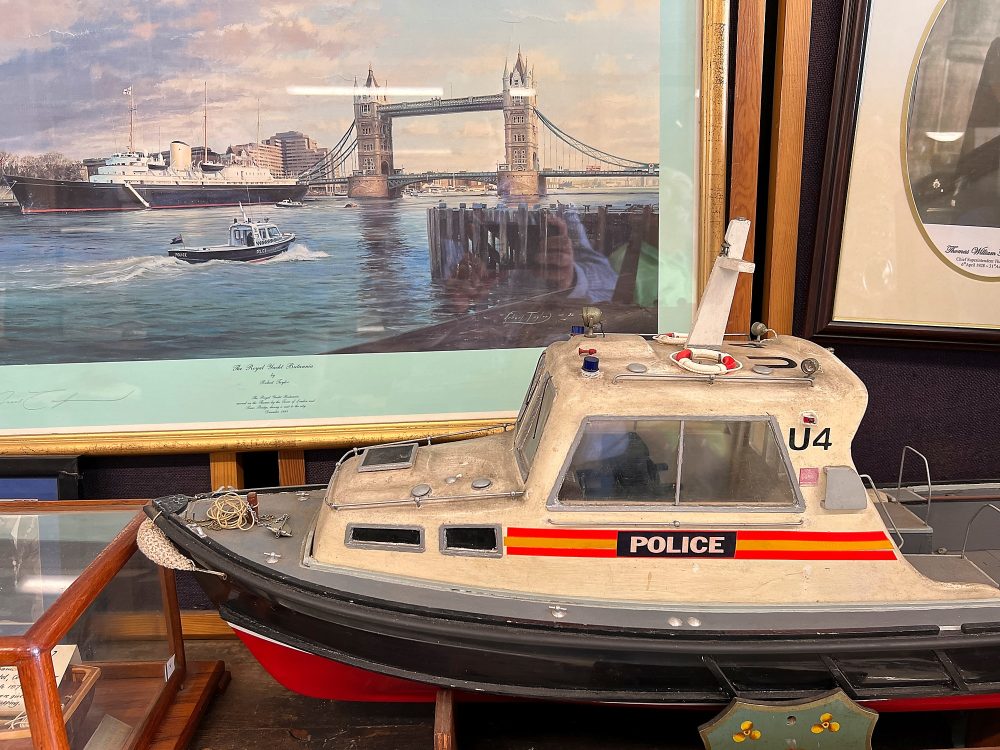

The Marine Police Force soon gained two steam launches and had eight in operation 20 years after the sinking of SS Princess Alice. There are photos of them in the Thames River Police Museum, along with the ensign from the Princess Alice.

Shortly after 1900 proper floating pontoons were introduced at Waterloo Pier, and Blackwall, and extra stations were set up at Barnes and Erith. Paraffin-engined patrol boats were introduced. The bombing in WW2 was obviously challenging.

The Marine Policing Unit today

The Marine Policing Unit (MPU) is still on the site where it was founded (back though several name changes) in 1798.

The MPU is now responsible for policing 47 miles of the River Thames in London between Dartford and Hampton Court. It also provides cover for other bodies of water across the rest of London, such as lakes, reservoirs and canals.

The Marine Policing Unit recently took delivery of 5 new Fast Patrol Vessels plus one larger Command and Control Vessel. It also has a range of Rigid Inflatable Boats, which I understand are the fastest boats on the river.

All MPU officers are highly trained in managing boats in the specific conditions encountered on the Thames.

Rob explained that they don’t have divers as seen in Jacques Cousteau films, swimming with fishes. A specialist underwater and confined spaces search team works throughout the Metropolitan Police District.

The unit also has 24 officers who are trained in rope access techniques, as in climbing aboard ships, and up mountains. They are trained to carry out searches and counter-demonstrator operations at height. Rob gave the example of a fathers’ rights protester who scaled the London eye in 2004, and Just Stop Oil protesters who climbed along the suspension wires of the Dartford Crossing in 2022. MPU officers had to risk their own lives bringing them down safely.

Including questions Robert Jeffries spent 90 minutes guiding us through the entire history of policing on the Thames. There was no detail that he didn’t seem to know. Despite living only 3 miles from the Thames River Police Museum most of this was new to me.

Rob said that during his time as an officer two big events stood out. The first was the Marchioness disaster in 1989 when a dredger hit a passenger vessel near Cannon Street Railway Bridge. Four Metropolitan Police patrol boats assisted in the rescue of 87 people, but fifty-one passengers died. Rob spent five days searching for and recovering victims. As a result the Government asked the PLA and the RNLI to work together to create a rescue service. Four new lifeboat stations were created.

The second big event Rob remembered was 9/11. He said that although this happened in New York, it changed policing everywhere: terrorism.

The Thames River Police is recognised as being the longest continuously serving police force in the world.

Thank you Rob – this was one of our best ever visits. To book a visit you’ll find the museum’s contact details here.

Alan Tucker